A personal account of Jan Jongert's 2023 Venice Biennale

Jan Jongert and Jeroen Bergsma, architects of Superuse Studios – which they describe as “a 25-year-old start-up” – first travelled to the Venice Biennale in 1991, when they were hitchhiking engineering students and fans of the ‘starchitects’ of the day. Fast forward to 2023 and the latest biennale, and Superuse itself provided the Dutch contribution, Plumbing the System. In his account of the making of this contribution, Jongert explores the changes that the field has undergone since 1991 in seven sketches. In a personal account, he describes how the Superuse intervention at the Rietveld Pavilion came about – from challenging conversations with numerous stakeholders, to a recalcitrant economic system, to the practical obstacles to a completely natural roof water retention system.

By

Jan Jongert,

28 November 2023

Words by Jan Jongert

My first visit to the Venice Biennale of Architecture was in 1991. I had hitchhiked to Venice with my friend Jeroen – now one of the Superuse partners – in less than 24 hours. It was a biennale edition that celebrated the rising ‘starchitects’ of the day – Koolhaas, Tschumi, Herzog & Meuron and Hadid – while James Stirling had just completed a new pavilion in the Giardini delle Biennale. It was a moment that strongly challenged the recent dominance of postmodern architecture. Nevertheless, the focus on buildings as the architect’s main production remained, and I must say that it inspired me during my early studies in Delft. The works presented proved that a wide variety of information and stories could inform the design and form of buildings, rather than (the search for) a unifying and dominant architectural style.

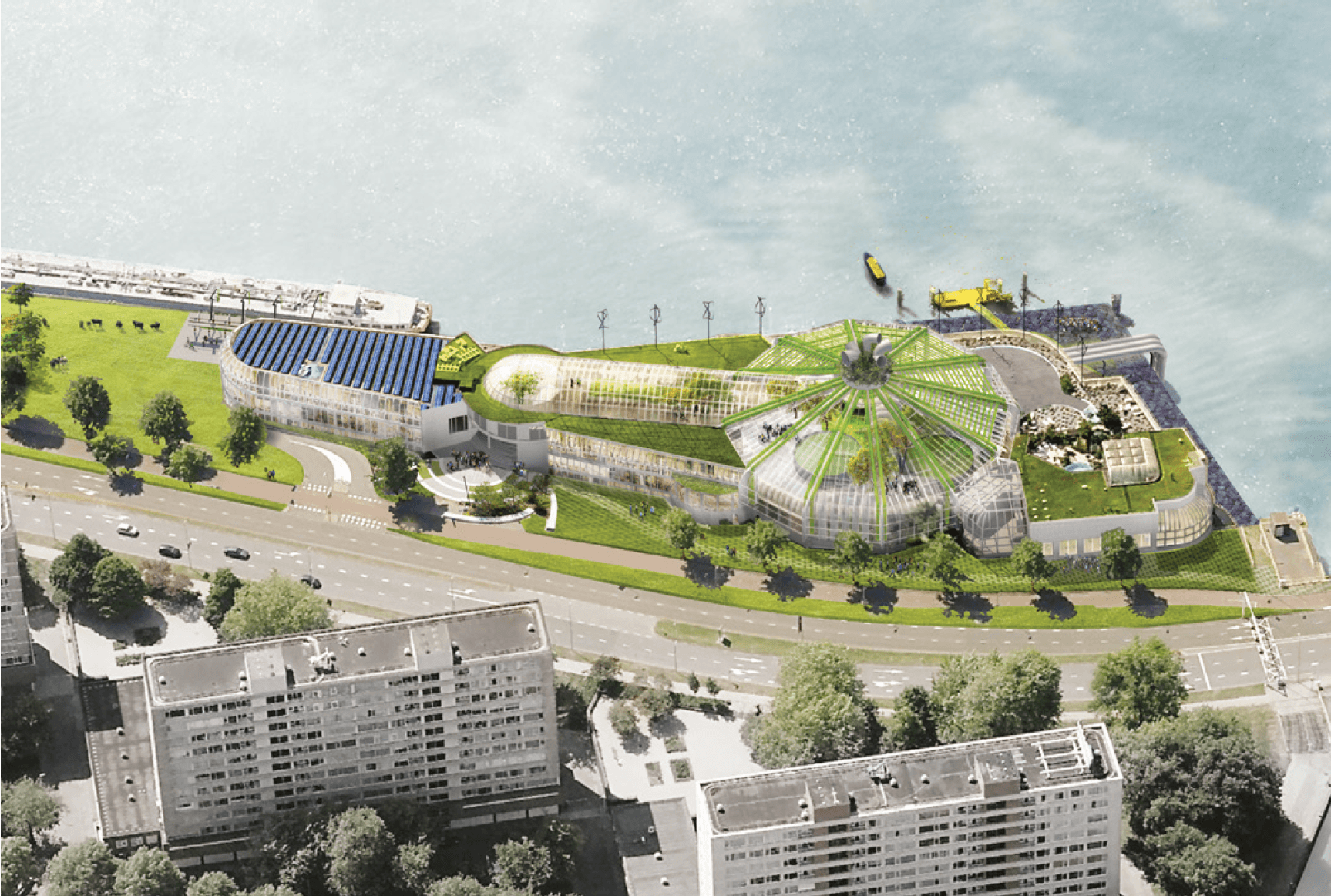

Thirty years later, the process of how architecture and buildings are created is receiving ever more attention and has become a leading story in architects’ presentations. With my office Superuse, I have designed and built a number of installations and buildings that express the process behind their development – particularly those constructed using reclaimed materials from deconstruction and industrial processes. In addition to material flows, we’re increasingly incorporating water, energy, air and nature flows into our projects, in order to reconnect them to the natural ecosystem.

When I was asked to curate the Dutch pavilion and bring this approach to Venice, with the theme Laboratory of the Future coined by curator Lesley Lokko, it was an exciting challenge, a great opportunity to bring today’s most urgent stories to the international stage and at the same time develop a Superuse intervention.

This is my account of the development of the intervention that Superuse contributed for the Dutch Pavilion of 2023.

Two water stories

After decades of pioneering work with Superuse, it has become clear that our economy does not support architects to be environmentally friendly. We have sometimes ridiculed these hidden constraints by calling ourselves “a 25-year-old start-up” while trying to change our professional context, rather than our business model. It is clear to me that the dynamic most in need of public discussion is the way that the economy shapes our built environment. This hidden power behind what architects do (and why) has been kept out of the public debate for too long: architects hide behind their professional limits of where they can and should have influence (Jacques Herzog in Domus, for instance). Carlijn Kingma, an architect educated in Delft, has dismissed these constraints, turning the complex workings of our economy and the role of finance into a spatial work. We showed her work The Waterworks of Money in the pavilion to frame and contextualise the architectural installation.

Carlijn and her research team use water as a metaphor for money: money that flows unequally through our society. This led me to the second layer. My study of flows taught me that there are two major untapped resources at the Venice Biennale: the 300,000 visitors passing through, and the 180,000 litres of water that fall on the roof each year. I could express these in a parallel storyline in the pavilion.

To bring the rainwater and the visitors together, the pavilion itself offered a great opportunity to inform and inspire visitors and create a local impact. A first idea was to provide each visitor with two bottles of drinking water – actually purified rainwater collected on the pavilion’s roof. But apart from the legal issues with that installation, it would be even more interesting to explore the possibilities of using the rainwater for purposes within the pavilion itself. Would it be possible to upgrade the Rietveld pavilion with a sustainable intervention that would provide multiple long-term benefits for future curators, the owner, the neighbours and the local ecosystem?

Two water retention roofs

Superuse is based in Bluecity (Rotterdam), a renowned hub for pioneering companies working towards a new economy. One of the companies that was founded there in 2016 was Metropolder. They have invented a roof that can both store water and grow plants. The advantage is that the roof can store water and feed a richer biodiversity than the commonly grown sedum. They turned their invention into a modular system that can be scaled up to industrial levels. Metropolder was acquired by the Wavin company in 2022. Today, they supply water-retaining roofs throughout the Netherlands and export them to countries all over the world.

Option 1: industrial water retention system for roofs

1 of 2

As we are based in the same building, we were able to discuss the possibility of developing a low-tech version of their roof for active communities. For a neigbouring community called Afrikaander Wijkcooperatie, we installed a prototype of this idea based on locally available waste materials such as fruit crates from the market, broken ceramic pots and wine bottle corks. We decided to show both options (one with imported materials and one with locally available materials) as prototypes of water retention systems, because we had missed the deadlines for approval to install something outside in the listed gardens of the Giardini.

Option 2: Do It Yourself water retention system for roof

1 of 2

Fun facts about the plants that would grow in the two test installations: we aimed to enhance the local biodiversity of both animals and plants. So we set out to buy the selected plants species locally. However, we soon learned that the plants that we could buy in Venice were actually grown in the Netherlands. We therefore ended up with a mix of both (plants bought in the Netherlands, and plants bought locally, although all were cultivated in the Netherlands) in our two mock-ups.

A third, all natural roof

To reconnect the Dutch Pavilion to the natural water cycle and its surroundings, we decided to team up with De Urbanisten, a Dutch architectural studio and the inventors of tidal parks, sponge gardens and water squares. Their urban interventions use the dynamics of water to enhance biodiversity and inspire urban design and to re-programme public space (the Giardini). Looking at the options for a water retention roof, urbanist Marit Janse and I felt that all the current options for water systems contain a lot of plastic. Would it be possible to develop an all-natural version of a retention roof, instead of recreating a natural cycle with artificial materials? Could we use the positive momentum of this upcoming exhibition to raise the bar and create a prototype in less than two months?

In both our practices, we had come across a company that has launched a new product called Peach Stone; the Nocciolo company buys these peach stones from the fruit industry, which considers them waste. We have found these pits to be one of the best performing soils for playgrounds and De Urbanisten had initial discussions with them about the possibility of using them for roofs. The peach stones can replace the plastic crates that form the usual base of the water roof. Nocciolo has also invented Waterbread: an all-natural ‘cracker’ made from natural fibres and clay. This product absorbs moisture and releases it slowly, allowing plants to drink longer during dry periods.

Option 3: Natural water retention system for roof

1 of 2

However, we still needed three more layers. While we are encouraging more wildlife with the roofs, the design requires a filter cloth to prevent mosquitoes from breeding too enthusiastically in the standing water. The newly established Hollands Wol Collectief (Dutch Wool Collective) had just produced felt in various densities, one of which one was suitable for layering on top of the peach stone. Because of the speed of the process, wool was also used to transport water from the bottom layer to the Waterbread. As a base layer, a root- and waterproof film is needed. Just two weeks before the opening, the Tefab company supplied us with their latest innovation: a sheet of bio-based membrane.

The 32 stakeholders

Carlijn and her team had created a spatial representation of all the actors and processes in our current economy and also presented three future perspectives of how a sustainable economy could work, creating more equal value for society. The three prototypes of water-collecting roofs nicely mirrored the three prototypes of future economies.

Compared to redesigning our economy, with its heavy regulation, global interconnectedness and large institutions, putting a green roof on a 250-m2 building seemed so simple. If only it were… In our preliminary discussions with Rob Docter, the director of the Rietveld Foundation which manages the pavilion, we learned that the Dutch pavilion would soon need renovating, as this was last done 30 years ago. We discussed the possibility of including the roof in the renovation plans, so solving some of the pavilion’s well-known problems, such as overheating.

Dear Jan, as long as you don’t disturb the water drainage and fix the hole(s) in the ceiling, there’s no problem. But watch out for the rainwater drainage which I think runs through the wall! Let Bouwko have a look at it please: cutting into or knocking holes in the walls seems like a bad idea to me. Best of luck, Rob.

After this enthusiastic kick-off, we realised that we needed an inventory of who else we needed to talk to in order to get our project approved. We did not foresee that a small building, in use for just six months a year, can generate a list of at least 32 stakeholders: from the Netherlands, of course, we have the owner, the Dutch Ministry of the Interior has a big say. As the pavilion is used for both the art and the architecture biennials, there are two institutional commissioners who work with the pavilion (the Nieuwe Instituut and the Mondriaan Fund) and the plans should not bother the future curators and exhibitors.

Then, on a local level, there is the Sopraintendenza, the local municipality, the heritage and monument commissions, the safety regulators and the building committees. We would need a local architect to apply for all the different permits. We would have to work with the city’s health and safety offices and ecologists if we wanted to reconnect the rainwater flow to the public space. We could not go ahead without the input and agreement of the neighbours. The Belgian and the Italian Pavilions are visible neighbours in the Giardini, but it is less well known that to the north of the pavilion, in a back alley, the building faces a social housing block. Residents use the back wall of the pavilion informally to dry their laundry. And we haven’t even mentioned the funders, all of whom will have their own ambitions and objectives built into their funding conditions.

The design of the renovation is not just a matter of construction or aesthetics; it is the start of a process involving many people and institutions, all of which need to be aligned. A design has to work to meet all these needs. This hidden aspect of design requires management and creativity on a completely different level than what is taught in schools. Our work became an exploration through the inventory we compiled.

In preparing our installation, new stakeholders became involved: WDJA architects from Rotterdam were able to introduce us to the technical details of the previous renovation in 1995, when they had installed technically innovative drains in order to remove rainwater as quickly as possible. They provided insights to study the idea of reversing that solution in a next renovation.

Hi Jan, thanks for the nice chat. We have the attached drawings of the Venice RVP immediately available. The ‘plan’ (including the roof plan with slope and rainwater drainage, and a plan for the sewer connections) is a revision drawing so should be reliable regarding the number, and a good indication regarding the positioning of these parts. It is possible that the contractor still had to submit drawings for the utility connections (allaciamento) at the time, that question can be asked. We may have more drawings from other consultants or the contractor in our paper archive but that will take some searching.... Kind regards, Wessel de Jonge.

The local architect from Venice, Pietro Vespigiani, gave an insight into the length and numbers of the processes: when we proposed drilling a hole in the back of the pavilion to create a visual connection with the hidden neighbours, he predicted about seven different agreements and several months of processing time.

Dear Jan, I am sorry, but the opening of an external hole, whether closed with bars or windows, is not at all simple. Venice is a city where the protection of institutions is absolute and it is no coincidence that much of the city is identical to late 18th-century Venice. To open a hole in an external wall, the authorisation process involves: 1) request for authorisation from the Superintendency of Historical Monuments (the pavilion is listed), 2) request for landscape authorisation (the entire historic centre has this constraint), 3) static certification for anti-seismic standards (mandatory for every new hole in load-bearing walls), 4) authorisation from the private building office of the Municipality of Venice. In addition, the external wall is not the sole property of the Holland Pavilion, but there is co-ownership with the Biennale Foundation, which would certainly not give the go-ahead. The installation of pipes, plants or anything else on the public road must have the same procedure (with the exception of seismic certification).

Test results

After four months and the first tropical temperatures, the natural roof test installation showed the worst results: the soil seemed driest of all and the plants looked unhappy or had partially died. Two observations as to what might have caused this: we saw fungi on the peach stones that could have negatively affected the plants. However, the fungi actually grow on the remains of the fruit, so rather than a negative result, it should be a positive contribution to the development of the soil. On further consideration, we realised that we should not have used the wool to transport water from the base to the plants. Wool is a good insulator – precisely because it does not conduct moisture and water. By using it, we had probably cut off our plants from their food source. A new version with a different material should easily solve this problem.

Out in the open

The renovation plans for the Rietveld Pavilion are too far in the future to bring the water retention roof closer to realisation. This has allowed us to continue testing the natural, peach-stone water retention set-up. As we aim for our contribution to the pavilion to make a positive impact, we of course wanted to use the time available to test the installation. In our opinion, the retention roof with natural materials deserved a second test outside. So we are using the the time dismantling the exhibition to set up a new installation. We will test it from the time the pavilion closes until next spring. In this way, we will both reduce the transport logistics of a team travelling to Venice to set it up and increase the practical knowledge of our innovation. Discussions are currently underway with the curator of the art biennial to see if parts of the exhibition can become part of the Dutch art presentation in 2024.

The first follow-up of our innovations is the request by the Dutch railway infrastructure company ProRail to test larger samples of four water retention roofs for 1500 technical buildings in the Netherlands. These will contribute to the future development of roofs that support biodiversity and climate adaptation, and which we hope to bring to Venice in the future.

Read more about Plumbing the System: