Nieuwe Instituut Acquires the Archive of Hannie and Aldo van Eyck for the National Collection

Nieuwe Instituut has acquired the archive of architects Aldo and Hannie van Eyck for the National Collection. The Van Eycks’ work is internationally important for its role in architectural innovation in the second half of the 20th century. Their projects include the influential Burgerweeshuis (Amsterdam Orphanage), the Pastor van Ars Church in The Hague and the Sonsbeek Pavilion in Arnhem. Financial support from the Mondriaan Fund and the Rembrandt Association enabled the purchase of the archive’s 23 models, while the remaining materials were donated by Tess van Eyck-Wickham.

4 August 2025

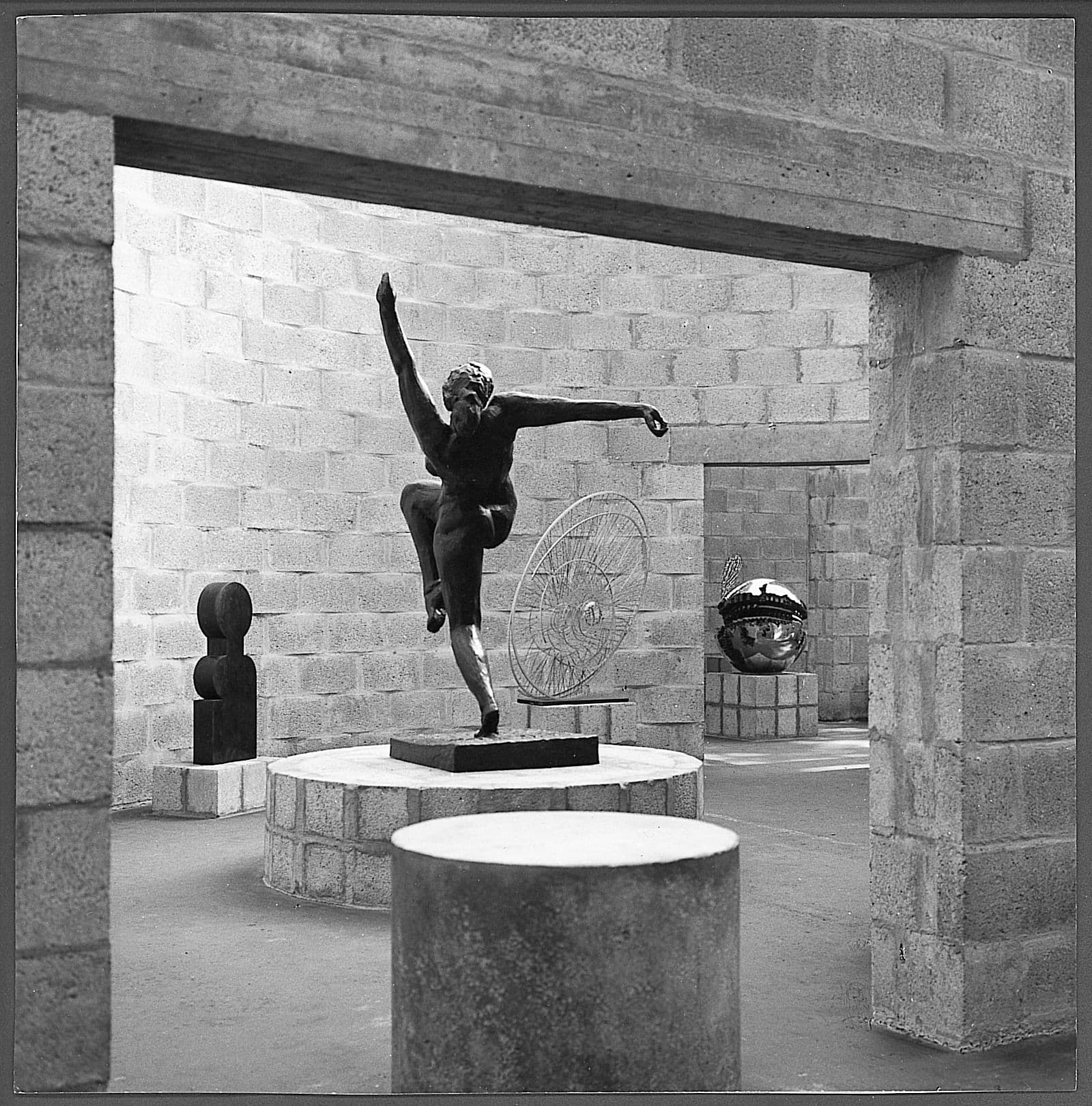

The archive contains models of landmark projects, including the Zeedijk Playground (1955), Burgerweehuis (1960) and Hubertus House (1980), all in Amsterdam; Wheels of Heaven in Driebergen (1963); the Sonsbeek Pavilion in Arnhem (1966); and the three primary schools in Nagele (1956). The new acquisition also contains design drawings such as those for the expansion of the court of audit building in The Hague (1997), as well as the urban renewal project for Amsterdam’s Nieuwmarkt neighbourhood, undertaken in collaboration with Theo Bosch in 1975.

A movement of renewal

Through the National Collection for Dutch Architecture and Urban Planning, the Nieuwe Instituut preserves the collective memory of Dutch architecture. Aldo and Hannie van Eyck play an unquestionably major role in this story. They were part of the post-war movement of renewal that sought an alternative to the prevailing modernist vision, which had led to a wholesale one-sided architecture with little room for individual expression. For the Van Eycks, it was essential to re-examine the avant-garde origins of modernism and radically expand it beyond the boundaries of the Western world.

Art as a source of inspiration

In their search for a new form of architecture, Aldo and Hannie van Eyck found an important source of inspiration in art, particularly Cubism and Surrealism. In the work of artists like Klee, Brancusi, Arp, Dali, Ernst and Mondrian, they discovered an aesthetic based not on a hierarchical order, but on the coexistence of equal elements. This in turn led them towards non-Western cultures, which inspired them in their quest to find a new identity for modern people who had lost touch with their environment.

Playgrounds

Both Aldo and Hannie van Eyck studied architecture at the ETH Zurich in Switzerland. On returning to the Netherlands, Aldo joined the urban development department of Amsterdam’s public works office, which was then headed by Cornelis van Eesteren. In 1947, he was commissioned, in collaboration with Jakoba Mulder, to provide every Amsterdam neighbourhood with a public playground. This gave him the opportunity to experiment with elementary forms and their interrelationships. Each playground was a unique composition of solid concrete elements and simple climbing frames made of tubular steel. These fixed objects invited children to move, rather than encouraging passive play like the moving objects that had generally been used in playgrounds before then. Between 1947 and 1978, Van Eyck designed around 700 playgrounds. He sometimes collaborated with visual artists, such as Joost van Rooijen, Hannie’s brother, and Constant Nieuwenhuys.

Dutch Structuralism

Aldo and Hannie van Eyck laid the foundations of Dutch Structuralism, an influential post-war architectural movement that emphasised encounter and connection in order to create a humane living environment. They did not use the term ‘structuralism’ themselves, preferring instead to speak of architecture as a ‘configurative discipline,’ focused on relationships and connections. The idea was that modern architecture should foster non-hierarchical relationship patterns by constantly provoking encounters. The maze-like structure of the Sonsbeek Pavilion (1966), for example, was designed to allow visitors to experience an almost spontaneous encounter with the exhibited works, and also with each other.

A younger generation recognised this vision as the impetus for a new modernism. In particular, the labyrinthine structure of the Burgerweeshuis, with its interconnected interior and exterior spaces, sparked a craze for the complex interlinking of buildings and urban spaces at Amsterdam’s Academy of Architecture, where Van Eyck taught from 1955 to 1959.

Dutch Structuralism is one of the most important contributions to 20th-century modernism, comparable to British Brutalism and Japanese Metabolism. These movements from the 1960s and 1970s are, like Structuralism, once again attracting great interest from new generations of students and researchers.

The Van Eyck archive aligns with the series of archives of Dutch Structuralist architects acquired in recent decades. These include those of students and former collaborators of Aldo and Hannie van Eyck, such as Joop van Stigt, Hans Tupker, Piet Blom, Theo Bosch and Jan Verhoeven. The archive of Herman Hertzberger, Aldo van Eyck’s co-editor at Forum magazine, is also part of the Nieuwe Instituut’s collection.

CIAM

Aldo van Eyck exerted a far-reaching influence not only through his design practice, but also through his publications and teaching activities. He lectured at the Rietveld Academie and the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam, and from 1966 to 1984 was a professor at TU Delft. He also gave frequent guest lectures and held teaching positions abroad. Through his participation in CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, 1928-1959) and Team 10 (1953-1981), he was one of the leading international voices of the post-war architectural vanguard. As editor of the magazine Forum in 1959 and 1963, he left a lasting mark on the development of modern architecture during that period.

The role of Hannie van Eyck

Whereas we previously referred to the archive as Aldo van Eyck’s, we now refer to it as Aldo and Hannie van Eyck’s, in recognition of Hannie’s contribution to the work. Officially a partner from 1983, she was actively involved in many of the firm’s projects even before then. She also attended most CIAM and Team 10 meetings. While Aldo van Eyck was a gifted speaker and writer in the public eye, Hannie was more of a quiet force behind the scenes. Following Aldo’s death in 1999, Hannie continued the practice, designing part of the Dutch contribution to the São Paulo Architecture Biennale (2000) and the Hunebedcentrum in Borger, Drenthe (2005).

The archive

The archive is exceptionally rich, informative and visually striking. As well as models, it contains design drawings from all stages of the design process, slides, photographs, audio tapes, travel films, project records, correspondence and texts. The archive offers several starting points for research that ties in with current architectural discussions. Examples include the preservation of recent heritage, which encompasses much Structuralist architecture; attention to female authorship in architecture; a shift in the approach to housing; and postcolonial perspectives in relation to Eurocentrism in Western architecture.

Over the next few years, the Nieuwe Instituut will prioritise cataloguing, preserving and digitising the archive so that it can be made accessible to the public, and available for research and extensive loans, as soon as possible. Plans are also being developed for various research projects and an exhibition dedicated to the work of Aldo and Hannie van Eyck.

The acquisition

The archive was transferred with the support of, and in close collaboration with, Tess van Eyck-Wickham, the daughter of Aldo and Hannie van Eyck. Part of the archive was acquired by the Dutch state under the inheritance tax exemption scheme. The models were purchased with the financial support of the Rembrandt Association (thanks in part to its Kruger Fund and its Friends Lottery Purchase Fund) and the Mondriaan Fund, the public fund for visual arts and heritage in the Netherlands and the Caribbean part of the kingdom.